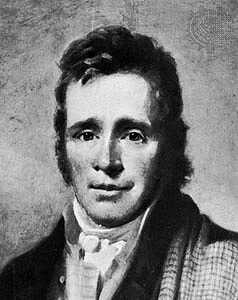

James Hogg

(My complete GMD bio/commentary

is here).

Bibliography

Scottish author, James Hogg (1770-1835), also known as the Ettrick Shepherd, was one of George MacDonald's primary influences. He first rose to prominence as an author with several books of poetry, but it was his anti-Calvinist novel, The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner, a book he wrote at the age of 54, that solidified his legendary status. None other of the few novels and shorts stories he wrote could even compare.

Memoirs and Confessions is the tale of two brothers, the elder, George, raised by his father and his father's mistress; the younger, Robert, raised by his mother and her friend (perhaps more than a friend), the pastor of the local Reformed Church--Reverend Wringhim. George's father obviously believes that Robert is the illegitimate son of Rev. Wringhim. The two boys go several years without seeing one another until one day Robert begins showing up at places where he somehow knows his brother George will be and tries to instigate a fight with him. George obliges him at first until he realizes it's his own brother he's fighting with. After this he tries to avoid fighting with Robert, but try as he might, Robert is relentless. Robert, having been raised under the strictest of Calvinist upbringings, believes (because his adopted father has told him so) that he can do nothing that will forfeit his eternal destiny to live in heaven as a Christian because it's something God had already decided upon before the world began. He also believes that he is nothing less the right hand of God and is just in punishing those he believes to be wicked.

The story takes on a very sinister turn when Robert one day comes upon a strange young man who goes by the name of Gil-Martin who in appearance looks exactly like himself--his doppelganger in every way. We later find that this Gil-Martin can take on the appearance of anybody. He says the ability is God's gift to him, and that when he takes on a person's appearance, he will also take on their thoughts, and thus know their minds. Robert is thunderstruck by the young man of whom he says, "...this singular and unaccountable being ... seemed to have more knowledge and information than all the persons I had ever known put together." Gil-Martin will suggest to Robert that he should kill several people in the service of God including his mother and brother, but his suggestions come in form like that of a preacher twisting biblical passages to diabolical ends. "They said ... Satan ... was the firmest believer in a' the truths of Christianity that was out o' heaven; an' that, sin' [since] the revolution that the gospel had turned sae [so] rife, he had been often driven to the shift o' preaching it himself, for the purpose o' getting some wrang [wrong] tenets introduced into it, and thereby turning it into blasphemy and ridicule." It becomes clear before long that Gil-Martin is none other than Satan himself, and Robert, after having done much killing for him, then tries to escape him throughout the rest of the story.

There are several elements in this tale that would affect many writers down the line: that of the doppelganger as an external (non-mental) living entity; the role of an evil being (Satan in this case) as being a shape shifter; an evil being (again Satan) giving people thoughts, even invading their dreams; and that of evil beings infiltrating good institutions (churches in this story), masquerading as instruments of goodwill and peace, while at the same time inserting a twist on dogma and then taking those dogmas to extremes, or even purposely acting out the role of a fool in order to make the organization itself appear foolish. This last in particular should give any Christian much to think about.

No one had ever before written anything along these lines in quite the same way James Hogg did. Obviously he was much affected by Hoffmann's The Devil's Elixirs. There are many elements that are the same in both stories, and Hogg's good friend, R.P. Gillies, translated an English version of the Hoffman novel for Blackwood Publishing (Hogg's publisher) that came out the same year as Memoirs and Confessions. However, where Memoirs and Confessions was a masterpiece of fiction, The Devil's Elixirs was quite pedestrian--even boring for many readers. Just as C.S. Lewis took The Golden Ass and rewrote it into something very different (and many would say considerably better, although The Golden Ass was quite good to begin with) in his novel, Till We Have Faces, so did James Hogg before him take The Devil's Elixirs and give it a Tour de Force. Part of the reason Elixirs is so grating is that it's a psychological drama. The doppelganger of Merdardus in Elixirs is something the narrator claims is generated by Merdardus himself mentally. This immediately gives it an air of fanciful humdrum. Robert's doppelganger in Memoirs and Confessions however, is seen together with Robert by several people. We know Gil-Martin is no figment of his imagination. Hogg giving his doppelganger time and space of his own makes him more dangerous to us all. None of this would be lost on George MacDonald. Many components of Memoirs and Confessions would make their way into MacDonald's own sphere of thought. And of course, he would share Hogg's antipathy toward the extreme tenets of Calvinism's predestination.

Something else MacDonald would be affected by in Hogg's writing was the poem Kilmeny. He mentions it in his children's novel--At the Back of the North Wind. It's a wonderful mystical tale of a young girl, Kilmeny, who wanders through the forest and ends up in another world, one very much like heaven at first, and for what seems like several years, yet when she returns home time has stood still and she has not aged at all. The notion mystics have of transcending not only material reality, but time itself, is another element MacDonald would use quite often in his stories.